20 May, 2020 By: Alex Forrest

Almost all car manufacturers and the suppliers that service them have been affected by the COVID-19 virus crisis.

The three countries that send the biggest number of vehicles to Australia are Japan (334,075 in 2019), Thailand (271,120) and South Korea (150,630).

In total, that’s approximately three quarters of all cars sold in Australia coming from these three countries.

Changes to the production of these vehicles and the parts for them are therefore set to potentially have an impact on Australian motorists.

Long before the outbreak of COVID-19, the demand for certain vehicles was already far outstripping supply.

Take the Toyota RAV4 for example. Since it was launched in May 2019, many customers have had to wait months for their new RAV4 Hybrid.

So while car supply issues are not new, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought a whole new set of potential changes to the availability of vehicles and vehicle parts.

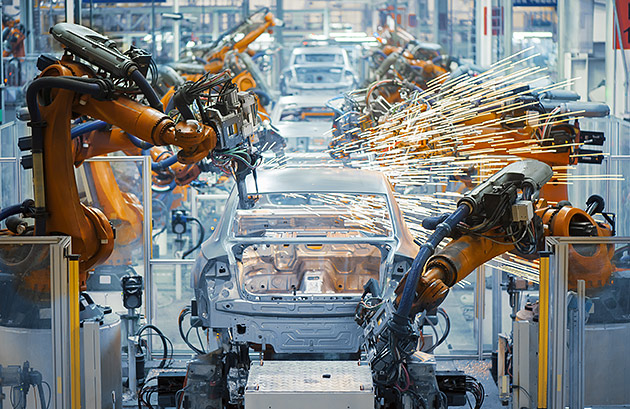

Some car factories have shut down, others have adapted their production lines to make medical products, while yet others are suffering parts shortages as their suppliers in the extraordinarily complex car-making supply chain begin to feel the effects of the pandemic.

For car makers, it is costly to buy and store large stockpiles of parts before they’re used in the factories that assemble vehicles, which is why manufacturers typically run very small stockpiles of components in their factory premises, with some components being delivered to factories only hours before they are needed.

What that means is that most factories, if they haven’t already been shut down or redeployed, have a limited capacity to absorb any interruptions to their supply of car parts.

While consumers considering buying a new car may postpone their purchase until after the pandemic has subsided, there will be an ongoing need to service and repair existing cars on our roads.

Vehicle workshops will still need to access service items like oil filters, air filters, oils and all the latest computerised tools and data. So, let’s look at just how all of this could affect you.

Impacts on motorists

Like any other business, car makers are keen to remain open for as long as possible while balancing their obligations around the health of their workers. But consumers should be aware that car makers will only announce bad news when it is absolutely essential, and sometimes not even then.

With that in mind, here’s what a selection of car makers in Australia have said about their plans during the COVID-19 crisis. The list is in descending order of the total number of vehicles sold in Australia in 2019.

Toyota

Toyota said its dealerships would remain open, with dealers continuing to provide essential vehicle service, sales and repairs in ways that prioritise customer health and safety, including increased cleaning and hygiene measures. Toyota is also pointing customers to digital platforms such as the MyToyota app and online service booking and sales, available through toyota.com.au and individual dealer websites (as at 23 March).

Mazda

Mazda said it has decided to adjust production at its facilities globally in consideration of difficulties in parts procurement, the plummeting sales in overseas markets, and the uncertainty of future sales. Mazda planned to suspend production for 13 days and operate daytime shifts only for eight days at its Hiroshima and Hofu plants in Japan between March 28 through to April 30. Similar arrangements are in place for its factories in Mexico and Thailand. Mazda has said it would abide by each of its export countries’ policies around preventing the spread of the virus.

Hyundai

Hyundai was one of the early respondents to the crisis, and suspended production back in February. The company said this was due to supply chain disruption directly caused by COVID-19 and was limited to Korea and China. By late March though, Hyundai said the supply issues impacting its operations in China and Korea had passed and all were back in operation.

Germany

German-built vehicles make up the next biggest source of vehicles sold in Australia. A total of 84,166 vehicles from Germany were sold in Australia in 2019.

However, Australians also buy German-branded cars that are built outside Germany, such as the BMW X5 (South Carolina, USA) and the Mercedes-Benz C-Class (South Africa). Include these, and the number of cars sold in Australia by the leading German brands from factories worldwide is 134,912.

In March, Volkswagen Group suspended production at its factories for VW branded vehicles in Germany, Slovakia, Spain, Portugal and England.

This includes factories which produce parts for these vehicles. BMW, which also includes the Mini brand, has said the spread of the coronavirus has “stopped growth in vehicle sales worldwide,” and that “we now expect our worldwide deliveries to decrease significantly from last year”.

However, BMW had yet to announce factory closures at the time of writing. Mercedes-Benz said it would suspend the majority of its production in Europe, as well as work being carried out in some of its offices, for an initial period of two weeks from 17 March, in line with recommendations of international, national and local authorities.

While Mercedes-Benz had made no announcements at the time of writing about its plants outside Germany, it did say that global supply chains would not be able to be maintained to their full extent.

United States

In the United States, the three major car makers there – Ford, General Motors and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) – had ceased production in the US at the time of writing.

Meanwhile, Ford suspended production in India, South Africa, Thailand, Vietnam, Europe and South America.

But Ford said its parts distribution centres would remain open to keep existing vehicles on the road, including those used by essential services.

Ford, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, Tesla, Nissan and General Motors have all either been approached about producing medical equipment or signalled their intent to move to the production of medical equipment.

What all of this means for motorists in Australia in terms of access to vehicles and parts is hard to tell, but one thing that is certain is that unprecedented changes have already been made further up the supply chain, and changes of that size could well be felt by Australian motorists.

Exactly how those changes flow down to the consumer level will be revealed down the road.

Pandemic pressure on fuel prices

By the time fuel comes out of the pump and into your car, its price has been determined by some of the most complex and wide-reaching set of influences of almost any commodity. These include global geographic and political factors, the value of the Australian dollar, local and international tax rates, local competition and even the seasons.

Now though, a major biological element has been added to the list of factors influencing fuel prices.

The highly contagious COVID-19 virus has wreaked havoc on lives and economies worldwide, including fuel prices. The onset of the virus in Australia in early 2020 was among several reasons for the significant fall in our petrol prices.

Leading up to the virus pandemic, demand for oil had already fallen by about 30 per cent, prompting Middle East oil producers to discount oil prices for customers in the US, Asia and Europe.

Then, as the spread of COVID-19 began to prompt further lockdowns and restrictions worldwide, oil production continued at rates that were too high for demand.

In Western Australia, oil price reductions were initially evident in falls in the wholesale price for petrol, which is the price fuel stations pay for the fuel they sell to motorists.

The retail margin is the difference between the wholesale price and the prices charged to motorists at fuel pumps.

But this difference only represents part of the potential profit fuel retailers make on fuel, because the exact amount they pay for fuel and its delivery to them is not disclosed and could well vary between retailers and brands.

While reductions in the amount consumers were paying for petrol in March 2020 were welcomed, the falls in wholesale pricing were, on average, markedly bigger than the reductions seen at the pump, indicating retailers weren’t passing on these price drops to motorists.

Fattening their margins for the sake of profit could be why fuel sellers weren’t passing on discounts to motorists, but the unique situation COVID-19 has generated, means there are other reasons why retail margins are blowing out.

For example, fuel retailers incorporating convenience stores can often find selling other consumer goods more profitable than fuel.

But with Federal Government guidelines to only travel when absolutely essential, these stores were likely seeing reduced foot traffic.

With overheads such as electricity, staff and maintenance still needing to be covered, it stands to reason some fuel sellers may be looking to fatter margins to make up for shortfalls in the shop and at the pumps.

Another reason is the potentially reduced volumes of fuel being sold due to lower demand for fuel in general.

Early reports indicate that, while demand for petrol fell, demand for diesel remained relatively high.

This is most likely due to the mining industry, heavy transport and other essential services continuing to operate during the COVID-19 crisis.

Still, at the time of writing, Perth’s petrol price cycle continued, with some price hikes widening retail margins hugely.

But even during unusual times, West Australians can continue to encourage healthy competition in our fuel market by using Fuelwatch to find the cheapest fuel near them and rewarding those retailers, while leaving the expensive ones alone.

Enjoy this story? Get more of the same delivered to your inbox. Sign up to For the Better eNews.