11 November, 2020 By: Ruth Callaghan

Each time you drive, your car’s powerful on-board computer systems are quietly generating details about the trip. Could this data be used to make our journeys better and safer and what are the risks?

It can happen in a split second. The road is wet, and you take a corner just a bit too fast, lose control of the car and spin out, hitting a tree.

At the moment of the crash you’re knocked unconscious and what happens next is out of your hands.

If a fellow traveller spots your car leaving the road, emergency services might be on their way within minutes. But if not, critical time that could be used to save your life will tick away.

If this scenario played out on a remote European road, the driver is likely to have some luck on their side.

Since 2018, all new cars in Europe have had a service known as eCall installed, which automatically detects when a crash has occurred.

As soon as the crash registers, the system dials an emergency service line and sends crucial information such as the time and location of the crash, and a description of the vehicle involved.

It is estimated by the European Union that eCall can speed up emergency response time by 40 per cent in urban areas and 50 per cent in the countryside, and it has the potential to save up to 2500 lives a year when fully deployed in Europe.

eCall is just one way the data being generated by vehicles could be used to help save lives, but Australia lacks a framework for collecting and sharing vehicle-generated data which would allow government to use it to improve road safety while protecting personal privacy.

The computer in your driveway

Right now, there is a computer sitting in your driveway that knows more about the way you drive than you do yourself.

But the question of what your car knows, and who it tells, is a complex one that raises issues not only of safety but of privacy and security.

And as the amount of vehicle-generated data grows, so does the need for clear rules around its collection, storage and use.

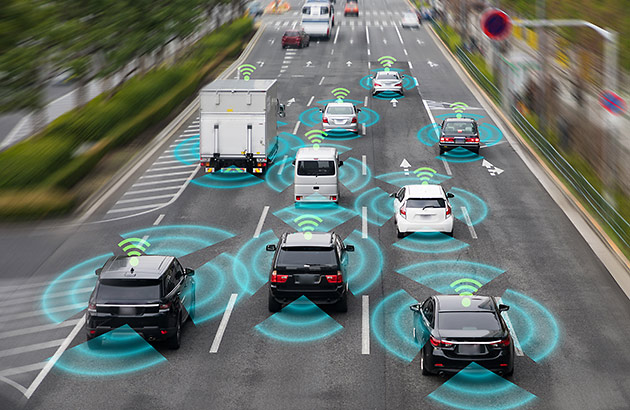

“We’re heading toward a more connected future, where cars will be connected to one another and to infrastructure,” says RAC general manager Public Policy and Mobility Anne Still.

“They will generate a lot of data, some of which will be personal data, but also other types of data that may be of interest to transport agencies.

To put a modern car’s computer into context, the average office computer has about 40 million lines of software code.“There’s really an issue here around just what data a car can collect, and then how that data is stored, how it’s used, and how it’s shared.”

That’s pretty big: almost twice the code that goes into an F35 fighter jet and 100 times that of a space shuttle.

But the family car computer is bigger.

RELATED:

How our cars have become more like computers »

Thanks to an explosion in the use of software in vehicles — driving the in-car entertainment system, tracking your blind spots, assessing your fuel efficiency — today’s cars are estimated to have up to 100 million lines of code and collect up to as much as 25 gigabytes of data per hour.

Tomorrow’s vehicles will be even smarter, with the use of software tipped to double by 2030.

From the tip of the tailpipe to the bumper on your bonnet, almost every part of a modern car is a data generating machine, capturing information every centimetre you travel on the road. The breadth of things your car already captures is remarkable.

Some of that data is external, including environmental conditions such as whether there is fog, or if the roads are wet. Some relates to the car itself, its oil temperature or tyre pressure.

Data can provide an insight into how the vehicle is being used: the speed at which you took that corner, the roads on which you drive, and the average load you’re carrying in the boot.

A brave new data world

Some of that data is available now, but to be collected, it is mostly limited to a physical download by your mechanic.

Within a few years, though, the stuff of science fiction will become fact, as the connection between different cars, and between cars and other sensors, becomes widespread.

Already cameras that face the driver are being trialled as manufacturers experiment with technology that links what is happening within the car with the world outside. BMW in January 2020 unveiled its new driver camera — a so-called ‘gaze detection system’ which can track what you’re looking at outside the car and engage you in conversation or provide you with information about it.

But the implications for road safety are also significant. Within a few years, not only could your car call for emergency assistance but it will be able to provide your surgeon with a real-time prediction of your risk of head injury.

Your car could alert sensors owned by the local council that a pothole has developed or receive an early warning from road authorities that there is debris on the road ahead.

A change in the pattern of your driving can let the vehicle know you’ve had a heart attack or even if your car has been stolen, so the car brings itself to a stop.

But while you might own your car, it’s not always clear who owns the data it produces, nor how you can define what is collected or how you give permission for who can share it.

From a governance perspective, that means most Australian agencies like first responders can’t gain information about a crash even if your car has an important story to tell. Road authorities can’t yet use car data to plan their infrastructure or monitor assets, and police (usually) can’t easily access vehicle data to understand the causes of a crash.

Personal privacy prompts concerns

RAC’s Anne Still says RAC members are divided on how they feel about vehicle data being shared, and as the data becomes more personal, their concerns increase.

In a survey of almost 600 members that looked at both vehicle and transport-related data, including information collected via public transport Smartrider cards, three- quarters were happy with road condition information being shared with government once it had been de-identified and aggregated.

A comparable proportion (71 per cent) were happy with data about the operation of vehicles immediately before and after fatal or serious crashes being shared with government, and two-thirds were happy for vehicle emissions data to be shared.

But they were less happy with the sharing of data that could potentially identify individuals.

Enjoying this story?

Sign up to our monthly eNews

Just 42 per cent were happy to share information about their location or the time of their car journeys, even if that data was summarised at a postcode level.

When it comes to any form of travel, 73 per cent were very concerned about their journeys being monitored. More than two-thirds were very or extremely concerned about data being used for purposes to which they had not consented.

The results of the survey were included in an RAC submission to the National Transport Commission (NTC) which is looking at the issue in more detail as it tries to develop a framework for how vehicle data should be treated for use by government.

Anne Still says the potential value of data for emergency service use and to improve road safety and network management is clear, but the concerns of drivers must be addressed.

“While there is that broad level of support for some use, nearly 90 per cent of respondents were concerned about data breaches, and that’s specifically related to identity fraud,” she says.

"Drivers need firstly to understand what data is being collected and for what purpose, and then they need the option to opt-out if they wish, without consequence. It shouldn’t mean any change to the performance of the vehicle or services they receive, wherever possible.

"We also have to keep in mind that the framework government puts in place needs to not only look at whether data is personal or not at the point of collection, but what happens once it’s shared and paired with other data, how it’s stored, and how it’s treated throughout the data lifecycle.”

Luis Gutierrez, manager productivity and safety at the National Transport Commission, says the NTC expects to report later this year on a recommendation for access to vehicle data, recognising that the absence of an agreed position on government access is a problem.

“Modern vehicles collect significant amounts of data that could assist government decision-making. However, Australia is at an early stage of development. Few vehicles today are connected, there are no agreed standards for data and governments have not agreed their data priorities,” he says.

The NTC’s goal is a national framework that can be agreed by both government and industry, so that data can be exchanged without raising commercial, privacy or security issues — or creating disincentives to deploying technology, he says.

“Apart from the need for public acceptance (and trust) of vehicle data being accessed, exchanged and used by government and industry, all the relevant parties need to agree on a framework for collecting, storing and exchanging data.”

In the meantime, RAC’s Anne Still says it remains important for drivers to be heard on their position about what data should be collected and shared for specific purposes, such as improving road safety.

“We have a window of opportunity in that vehicle connectivity is not yet wide- spread but within the next decade, we’ll have a situation where the majority of new cars are connected, and are down- loading and recording data,” she says.

“We need to get in front of that change.”

How RAC is helping to drive a safer future

RAC's Automated Vehicle Program is trialling new technology that will help save lives on our roads, reduce congestion and create more connected, sustainable communities.